Islamist Extremism The Rise of a Terror Threat

Extremism is one of the biggest threats to international peace, security and development.

While 9/11 was to become a seminal moment in the way the West viewed the threat of Islamist extremism, the attacks were never the start of the story. Many decades before and since 2001, millions have been affected by terrorist attacks perpetrated by jihadists while generations have become enthralled by the narratives that underly this militancy. The narratives may differ but too often they share common themes: The West is an aggressor on Muslims, Islamic governance must be restored to Muslim lands, and non-believers, including Muslims who emulate the lifestyles of non-Muslims, are an enduring enemy to Islam.

The rise of Islamist extremism, and how it has gained prominence in societies around the world, must be fully understood before it can be tackled and the threat diminished.

Pre-9/11 The Holy War

The 1924 collapse of the Ottoman Empire (the last Islamic caliphate) paves the way for the formation of new nation-states. Rifts long in the making – about the place of Islam in the modern era – are brought to the surface, creating the conditions for an enduring battle that will span religion, identity, power and the relationship of the Muslim world to the West.

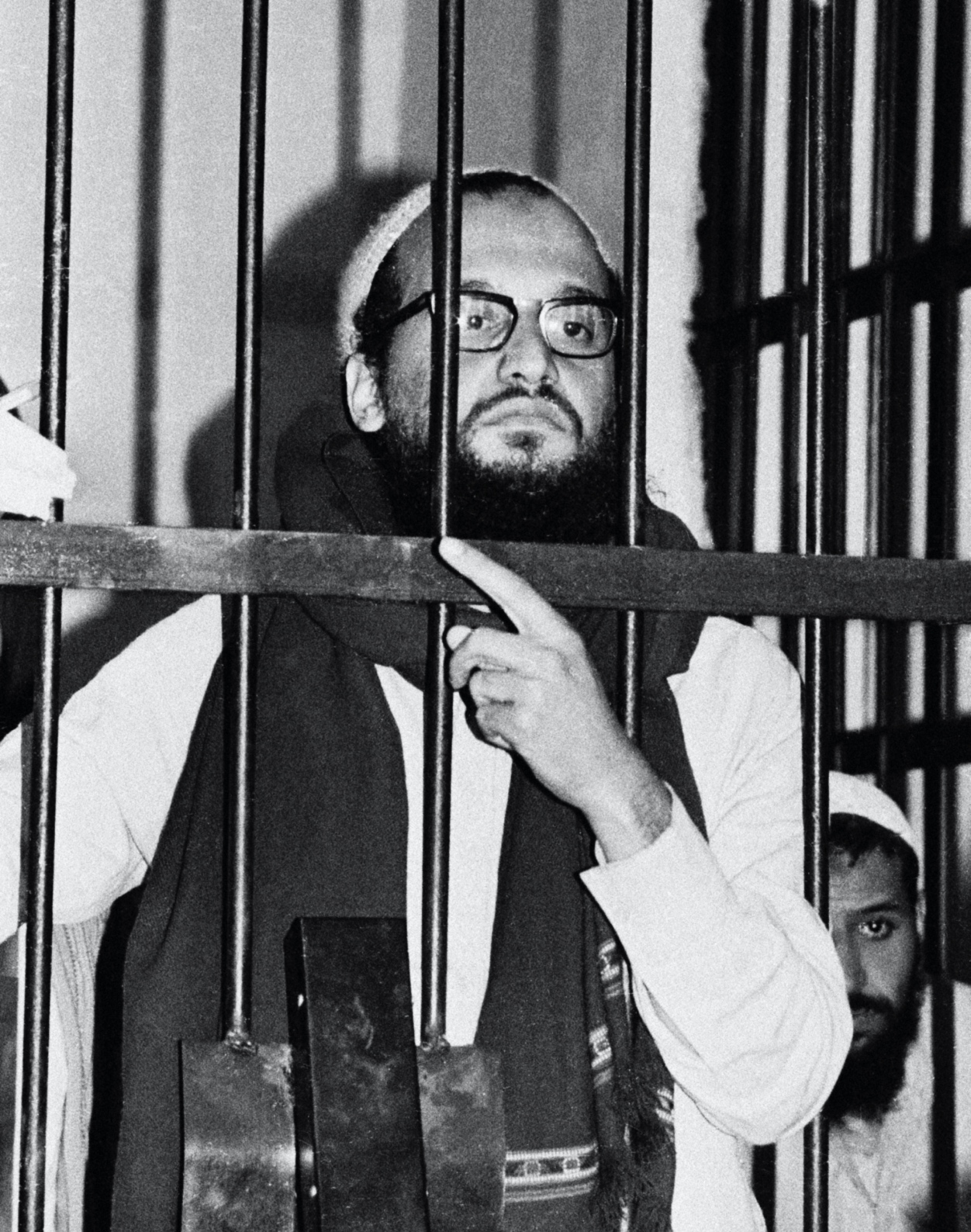

Amid this tumult, ultra-conservative, anti-Western movements take shape. From the 1940s, ideologues like Hassan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb aspire to the restoration of Islamic government and a caliphate through violence. The Arab-Israeli wars harden political thought further into the embryonic phases of modern terrorism while radical Palestinian terrorists, who oppose the creation of Israel, are behind kidnappings, suicide bombings and shootings. From the 1970s, Islamism is catapulted into the spotlight, with violence in the name of religion proliferating.

Proving a milestone, 1979 sees an escalation in international terrorism and extremism.

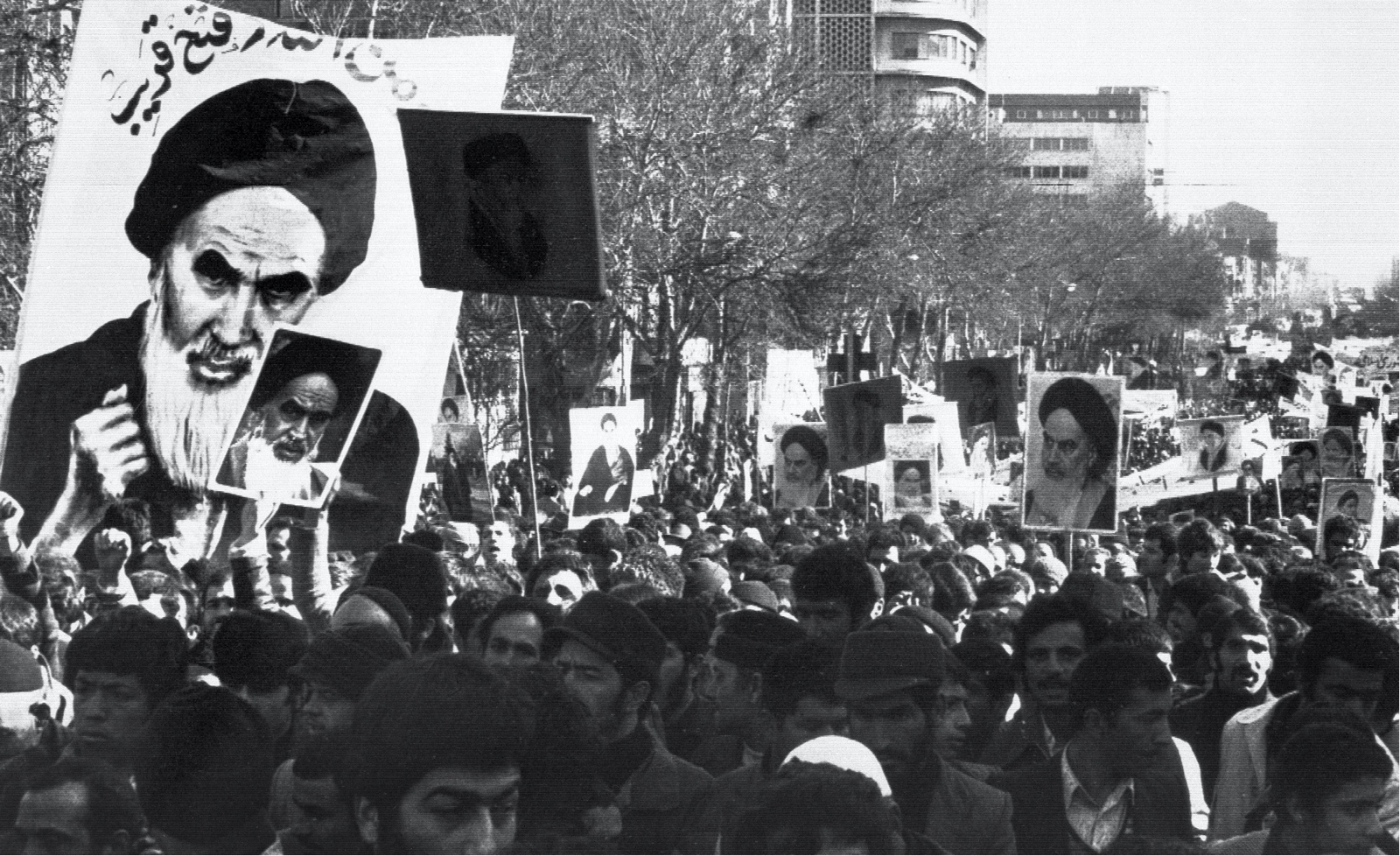

The success of Ayatollah Khomeini in toppling the Western-backed shah through an Islamic Revolution in Iran, transforms aspirations of political Islamist governance into reality for the first time. Khomeini and his followers set out to export their revolution to other Muslim nations and eradicate the State of Israel. In so doing, they galvanise Islamist militancy around the world.

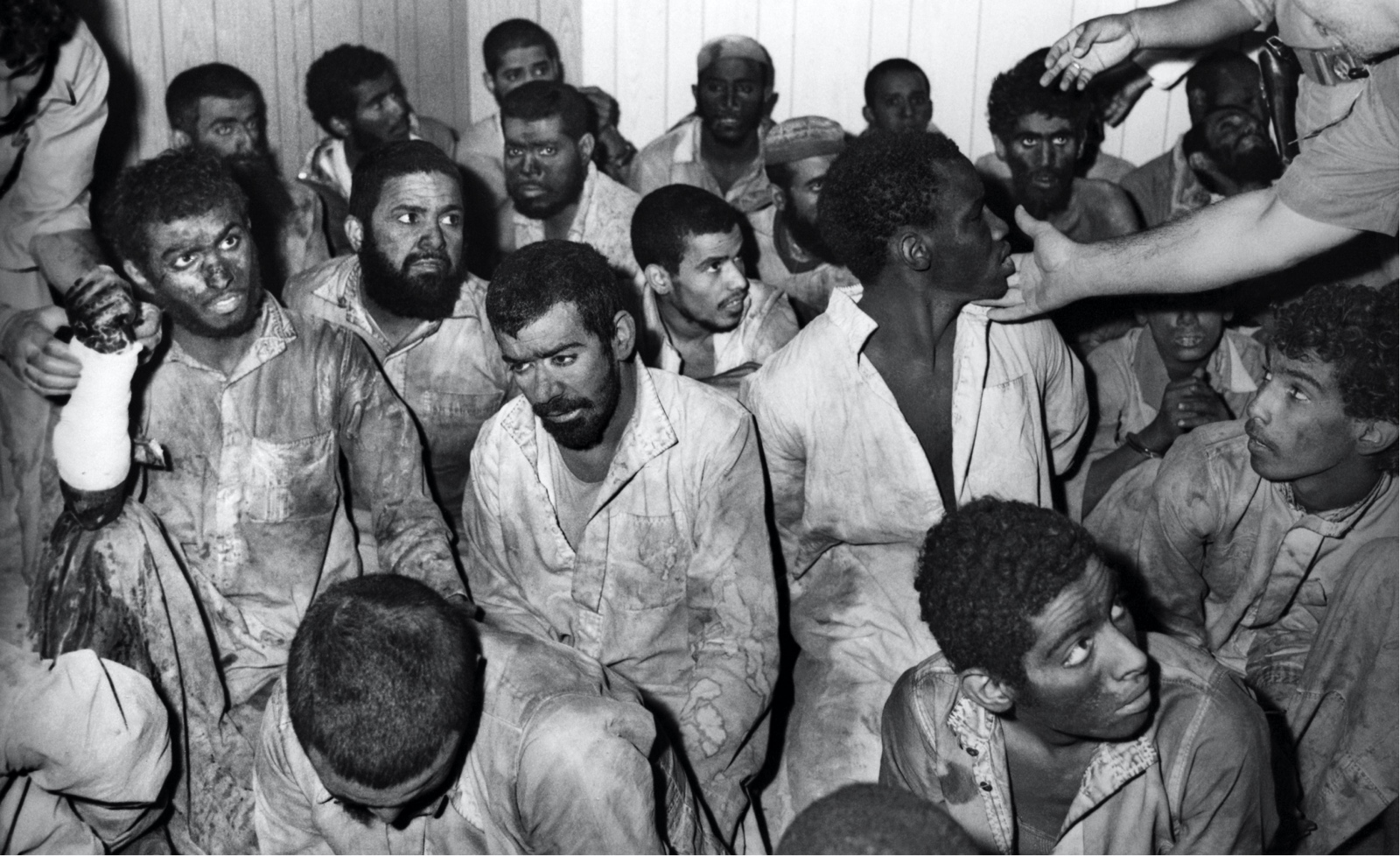

Inspired by events in Iran, up to 500 radical Islamists are involved in a siege of Islam’s holiest site – Mecca.

They advocate a return to the “original” ways of Islam, a repudiation of the West and expulsion of non-Muslims from Muslim lands. The incident in Saudi Arabia, and everything it symbolises, spurs on the international spread of extremist Islamist ideologies.

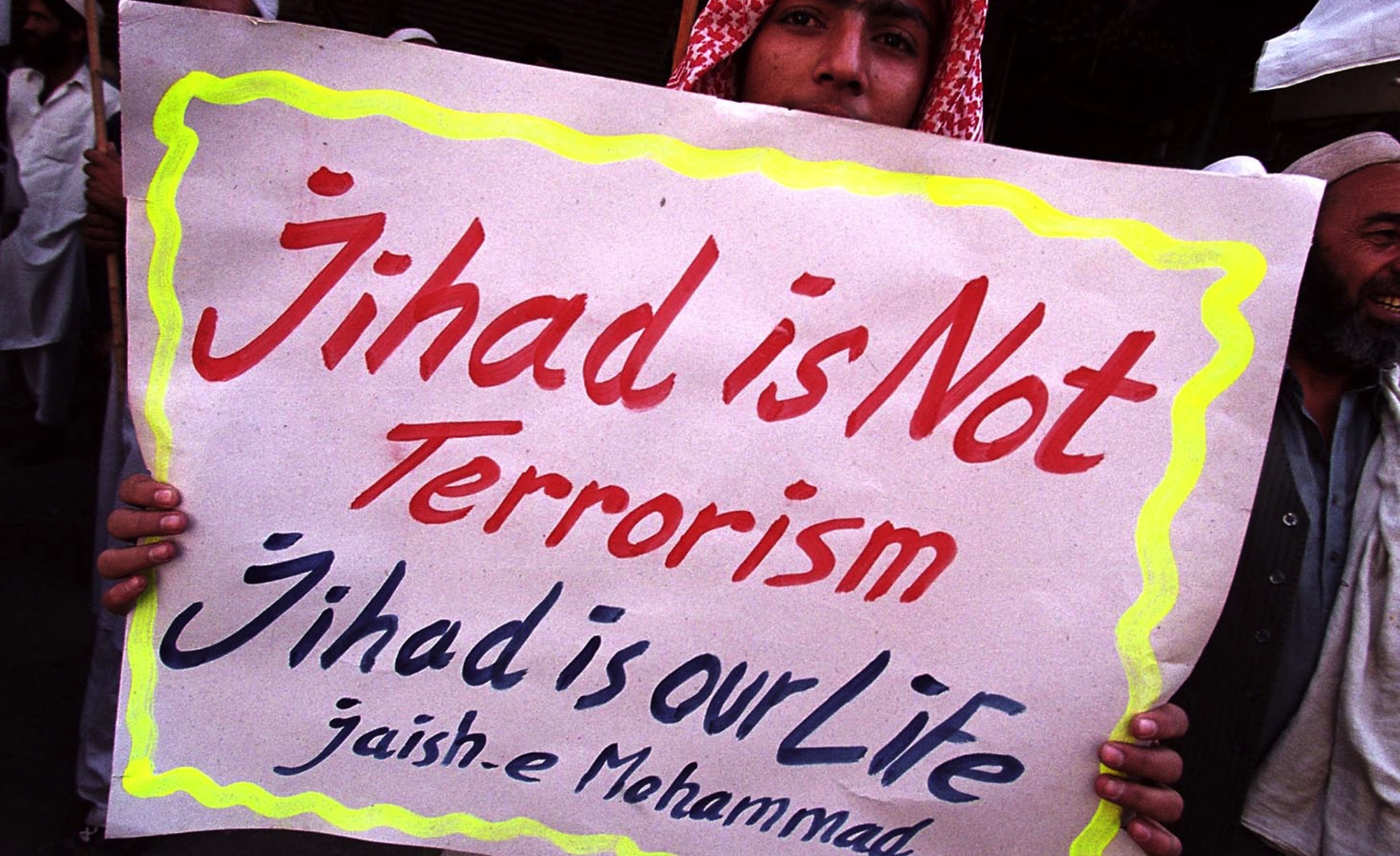

Soon after, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan attracts anti-communist Muslim resistance from all parts of the world. As armed Islamists flock to fight, Afghanistan becomes a seismic networking event and the arena for modern-day jihad. Resisting the Soviet incursion is now a matter of holy war.

Numerous groups assemble from ethnic Afghans to Arabs who travel from other countries. Among them is Osama bin Laden whose mujahideen contingent later evolves into al-Qaeda. With military and financial support from Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the US, the Afghan mujahideen becomes a resolute battalion. Soviet troops withdraw in defeat from Afghanistan in early 1989.

The success of the Afghan mujahideen on the battlefield, coupled with high-profile militant attacks elsewhere, convince many that jihad is a viable means to achieving political goals. The idea of protecting Muslim identity also comes into focus. Following the genocide of Muslims in the Bosnian war of 1992–1995, tensions between Muslims and non-Muslims communities are inflamed. Volunteer fighters from Muslim-majority countries join Bosnian Islamic brigades to battle opposition Serbian forces.

Similarly, Muslim Tuaregs and Somali Islamists take up arms in Africa against the symbolic borders of colonialism; Hizbullah launches suicide attacks on Israeli positions around the world; and Muslim separatists from Mindanao island in the Philippines engage in jihad against state forces who are perceived as oppressors of the Islamic faith.

The belief that Western governments are malevolent and un-Islamic drives armed Islamists to commit acts of terrorism.

In 1993, a truck bomb is detonated below the North Tower of the World Trade Centre, killing six. According to the main perpetrator Ramzi Yousef, the attack is in retaliation for

“the American political, economic and military support to Israel, the state of terrorism, and to the rest of the dictator countries in the region."

Despite financial support from the Soviets, Afghanistan remains in civil war. Mujahideen militants, Afghan warlords and tribal leaders are in charge of anti-government factions across the nation.

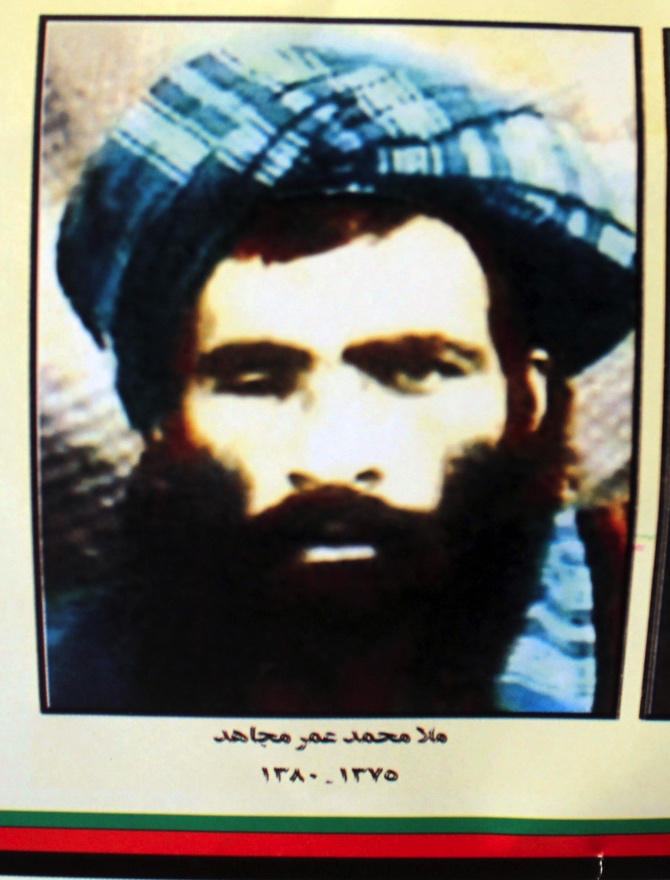

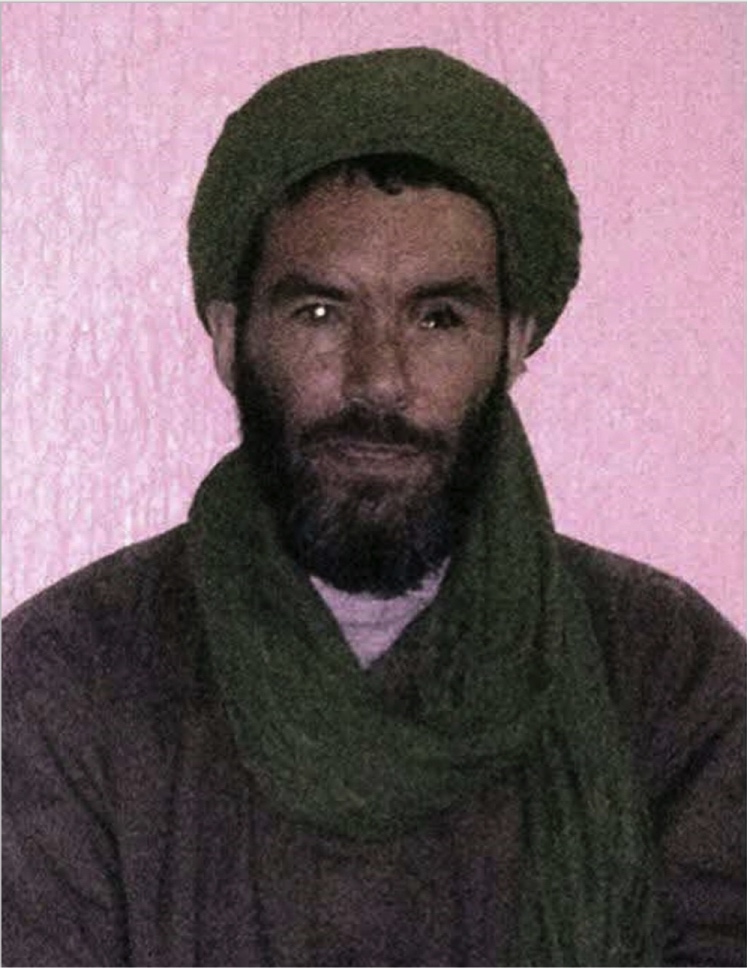

Former mujahideen fighters and Sunni students from Pashtun areas of Afghanistan form the Taliban in 1994, taking control of Kandahar City after successfully defeating the Afghan military. The group quickly gains popular support by reducing crime and stamping out corruption, eventually gaining control of a further 12 Afghan provinces by February 1995.

Like many other political leaders, President Burhanuddin Rabbani underestimates the group, considering them just a lawless band of ethnic Pashtun students capable only of guerrilla warfare. In September 1996, that same group seizes control of Kabul, deposing Rabbani and forcing him into exile. Taliban militants declare Afghanistan an “Islamic Emirate” and impose radical interpretations of sharia law combined with Pashtunwali tribal code on the population.

Life Under the Taliban

The Taliban’s ultra-extreme sharia policies return Afghanistan to the dark ages.

Alcohol is strictly forbidden, television banned and theatres converted into mosques. Christian communities are forced into second-class citizenship as a result of “dhimmi” pacts while Shias face discriminatory abuse and violence from the predominantly Sunni Muslim militants.

Hindus are forced to wear identity badges, which become likened to Nazi Germany.

Those convicted on charges of theft face amputation while women are systematically subjugated, unable to attend school and forced into “purdah” – physical and social segregation symbolised by the wearing of full body coverings.

The Taliban’s governance is also influenced by the religious edicts of Mohammed Omar, a former mujahideen who draws on the work of Osama bin Laden and other Salafi-jihadists to justify violence as the means to return to authentic Islamic rule – under the edict of original teachings and texts. Following victory, Taliban spokesman Mullah Wakil proclaims:

“We want to live a life like the Prophet lived 1,400 years ago, and jihad is our right. We want to recreate the time of the Prophet.”

As the Taliban regime presides over the Afghan people, Osama bin Laden – perceived a “hero of jihad” among the mujahideen – issues two declarations of war against Americans, Jews and Crusaders. Including signatories from armed Islamist groups in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, the message is clear:

“Fight the pagans all together … until there is no more tumult or oppression.”

In 1998, Al-Qaeda bomb the US Embassy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, killing 224

In 2000, the group attacks the USS Cole. 17 are killed

2001 - 2003 Call to Arms

On 11 September 2001, within the space of 20 minutes, two hijacked planes strike the two towers of New York’s World Trade Center. The towers collapse. Another hijacked jet is flown directly into the Pentagon while a fourth fails to reach its target and crashes into a field in Pennsylvania. Almost 3,000 lives are lost on US soil.

The world changes forever on September 11th, 2001.

The horror of these coordinated attacks unfolds on television screens across the world.

Never in its history has the US, or the wider Western world, been the target of such an attack.

After days of shock and mourning, the US identifies those responsible for the 9/11 attacks: Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda. The Taliban regime in Afghanistan is implicated in providing sanctuary for bin Laden and, by the end of September, American and British forces are deployed to the country. Surrender bin Laden or face destruction, the Taliban is told.

From his base in Kandahar, Taliban founder Mohammed Omar and self-proclaimed “Commander of the Faithful of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” responds by calling the world’s Muslims to join him in jihad against the US and its allies. In a televised message to the world on 7 October, bin Laden states in exultation:

“Allah has blessed a vanguard group of Muslims, the spearhead of Islam, to destroy America.”

From November 2001, the Taliban is driven out of Afghanistan by the Northern Alliance, the US and its allies. Al-Qaeda militants, including the notorious Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and strategist Saif al-Adel, flee to Iran before eventually moving base to Iraq, where the US are considering invading to depose Saddam Hussein.

Zarqawi establishes a network of militants in Iraq and leads his group Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad on a campaign of suicide bombings, executions and kidnappings. Iraq is viewed as an opportunity by al-Qaeda to plunge the US into a new conflict and, in so doing, relieve the pressure against militants in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Zarqawi accepts the assignment with enthusiasm since it provides a near-perfect breeding ground for his deeply anti-Shia world view. Zarqawi becomes known as the “Sheikh of the Slaughterers” among his supporters.

Galvanised by the 9/11 attacks, Islamist extremist movements experience a renewed sense of purpose on the global stage.

On 12 October 2002, jihadists belonging to Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) detonate bombs at four tourist hotspots in Bali in a coordinated attack, which kills 202 and leaves a further 209 injured. It is the deadliest such attack in Indonesia’s history.

Established in 1969 as a confederation of radical Islamic groups, JI’s ideological godfather, the radical cleric Abu Bakar Bashir states after the bombings:

“I support Osama bin Laden’s struggle because his is the true struggle to uphold Islam.”

Around the world, Islamist extremists step up similar offensives. Shamil Basayev, a former mujahideen and anti-Russian Chechen, takes responsibility for the deaths of over 160 people in four separate terrorist attacks across Russia in 2003; Kenya suffers its first major terrorist incident since the 1998 attack on the US embassy when Somalian militants target an Israeli-owned hotel and charter flight; and former mujahideen veterans orchestrate bombings in Morocco’s Casablanca, also in 2003.

There is a new dawn of Islamist extremist groups around the world since bin Laden’s call to take up arms.

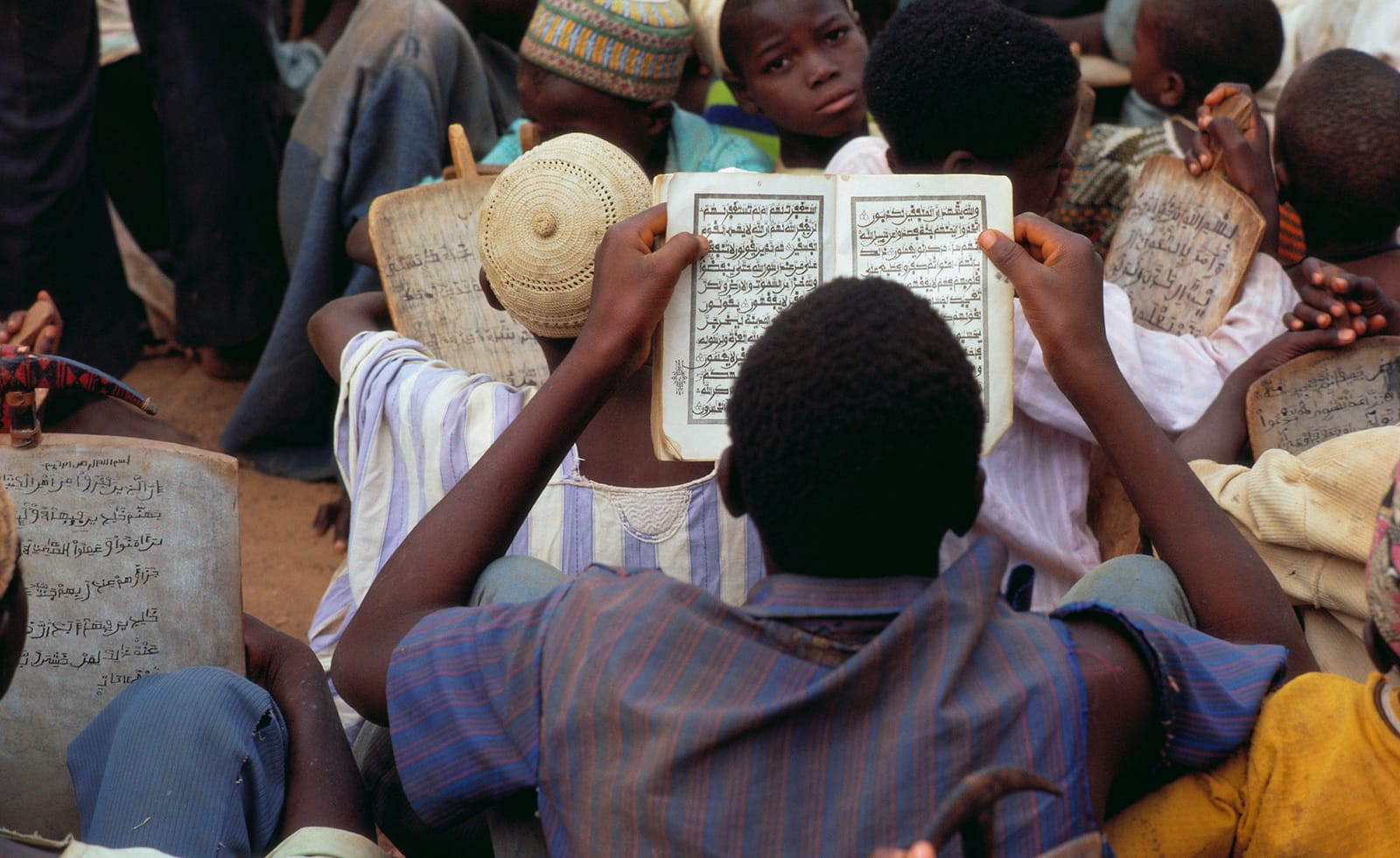

In early 2003, after years of criticising secular values and preaching radical sermons in the mosques of Maiduguri, Muhammed Yusuf, Muhammed Ali, Mamman Nur and Abubakar Shekau establish Boko Haram – translated from the Hausa language, it means, “Western education is forbidden.”

In their book, Muhammed Yusuf’s sons claim that 9/11 was the major inspiration behind their father’s decision to establish Boko Haram. The group’s quest for an Islamic state and eradication of Western influence results in them being dubbed by locals as the “Nigerian Taliban”.

2003 - 2009 Hearts and Minds

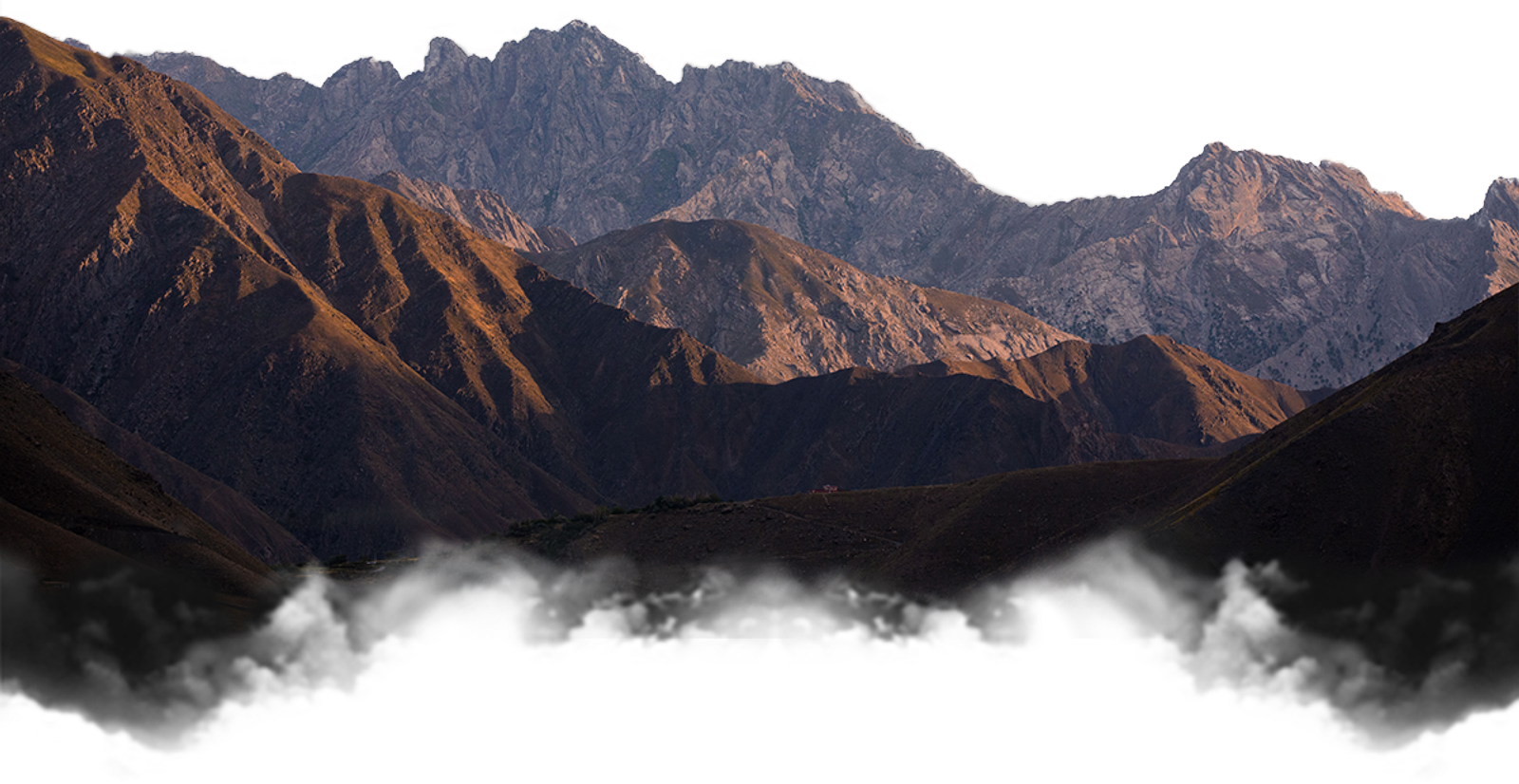

The US establishes the Afghan Central Corps headquarters while the Afghan National Army also starts to increase in size, supported by international forces who provide training. Eventually, the Taliban is forced out of major cities but members regroup and head to the mountainous regions bordering Pakistan.

In response to this defeat, Mullah Omar reconstitutes the group as an insurgent guerrilla force, resulting in waves of raids, ambushes and car bombings in urban parts of the country. Over in Iraq, Zarqawi formally pledges allegiance to Osama bin Laden, forming al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and attracting an influx of foreign fighters. Terrorist activities in Iraq intensify.

Global jihadists simultaneously escalate their violent campaigns. After 16 years of operational activity in the Philippines, Abu Sayyaf bombs the Superferry in Manila Bay on 27 February 2004, claiming responsibility. A total of 116 people are killed in the nation’s deadliest attack and worst maritime terrorist incident in history. Just as Bosnia’s jihadists claim to fight on behalf of oppressed Muslims, Abu Sayyaf states that the bombings are “revenge for the Muslims in Mindanao [Philippines].” Within three years of al-Qaeda orchestrating 9/11, the cities of Madrid and London, and the Philippines and Indonesia, all record their deadliest ever terror attacks.

Following the death of Zarqawi (AQI’s leader), al-Qaeda establishes a new Iraqi operation – the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). The group immediately absorbs jihadist factions from central and western Sunni-dominated parts of Iraq and continues to pursue the sectarian agenda outlined by Zarqawi.

One month after its formation, at least 215 people, mainly Shia, are killed in a series of bombings in Sadr City. This becomes one of the deadliest sectarian terrorist attacks of all time.

As the world starts to recognise the threat posed by Islamist terrorism, militants advance their state-building and governance ambitions. Violence is now just one aspect of the global terrorist problem.

By offering free food, other resources, money, education and even medical support, terrorists begin to win the hearts and minds of local populations. Four years after the Bali bombings, JI militants provide disaster-relief support to tsunami victims; Boko Haram delivers food and resources to populations in their territorial sphere around the Lake Chad Basin; and Tuareg Islamist commanders, such as Iyad ag Ghali and Mahmoud Dicko, ramp up their philanthropic efforts across Mali to ensure their violent, military re-Islamisation of the Sahel endures.

Terrorists are taking popular support away from incumbent governments and building armies of loyal, radical jihadists to further their pursuit of an Islamic State.

Beginnings of

al-Shabaab

Islamist militias break away from the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia and assume the role of community leaders in 2006. Al-Shabab and its associated pursuit of an Islamic State is taking root.

Beginnings of AQIM and JNIM

The Algerian terrorist group, the GSPC, which had previously identified Spain, France and US as primary targets evolves into al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

Despite now operating as a guerrilla insurgency, the Taliban maintains strong control in large parts of Afghanistan.

Its doctrine is as brutal as ever, with citizens forced to abide by its strict and fundamentalist world view. Non-conformists are tortured and paraded through the streets while alleged thieves are publicly punished with amputations.

Captured opposition forces are, in most cases, executed.

Letters are also being left in homes, public places, roadsides and mosques, threatening citizens and communities from engaging in certain activities prohibited by the Taliban. Among those to receive these “night letters” are teachers, students and their parents.

The Taliban’s ban on female education continues after the fall of its power base. At least 17 assassinations of teachers and education officials are documented in 2005 and 2006. Many of them were threatened by the night letters.

Those attempting to reach vulnerable Afghan populations also face assault and threats. In 2008, at least 29 aid workers are killed by the Taliban including a British woman, Gayle Williams. The Taliban states she was murdered because her organisation “was preaching Christianity in Afghanistan”.

In the years following 9/11, anti-western and anti-state rhetoric becomes virulently employed by global jihadist groups.

Six years after officially forming, and over 20 years since its founders all set foot in Maiduguri, Boko Haram launches its first ever terrorist attack on 26 July 2009.

Lasting three days, the uprisings aimed at eroding legitimacy of the Nigerian government, kill over 600 people in Borno, and inaugurates Boko Haram as the deadliest terrorist group in Africa.

Its founder, Mohammed Yusuf, is summarily captured and executed, but the group reassemble in the immediate aftermath of the attacks.

2010 - 2012 A Revolution Springs

In February 2010, Said Ali al-Shihri, the deputy leader of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), calls for a regional holy war. Just three months later, during the launch of his first National Security Strategy, US President Obama advocates for Islamist extremism to be referenced more widely: “Our nation is at war, against a far-reaching network of violence and hatred.”

Islamist extremism, and its terrorist manifestations, is now rising at an unprecedented rate. The pursuit of an Islamic State, coupled with the erosion of social, political and economic will, is turning into the universal agenda of violent jihadist groups worldwide.

In Indonesia, jihadists inspired by Abu Bakar Bashir, architect of the Bali bombings, assemble the East Indonesia Mujahideen in 2010. Gaining substantial local support, a regional narrative for the group takes shape as it seeks to establish the Islamic state once envisioned by the armed rebels of Darul Islam in the aftermath of Indonesia gaining independence in 1945.

Similarly, Boko Haram members continue to be inspired by their late founder Muhammed Yusuf and his vision for an Islamic state across West Africa. With Abubakar Shekau now in charge, the group breaks 700 Boko Haram inmates out of prison on 7 September 2010. On Christmas Eve of the same year, militants detonate four bombs in Jos City, killing over 30 people. Despite this, Boko Haram along with other violent jihadist groups rooted in societies across Africa, the Middle East and Asia are regarded by some as “pillars of society” and viable substitutes for elected government officials and politicians.

Deepening grievances towards incumbent regimes mark the dawning of a new decade, with nations around the world continuing to reel from the global financial crash of 2008. On 17 December 2010, Mohamed Bouazizi, a young impoverished Tunisian who sells fruit and vegetables to support his family, sets himself on fire to demonstrate against police harassment, the cost of living, corruption and President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali’s regime.

The event escalates and inspires a wave of protests across the Arab world, as millions unite to revolt against corruption, unemployment, poverty and authoritarianism.

Uprisings and Revolutions

Just 11 days after the first protests in Tunisia, uprisings intensify across Algeria, eventually bringing an end to the 19-year-long state of emergency imposed by the government in the country. Now known as the “Arab Spring”, the protests continue into 2011 with anti-Mubarak protestors flooding Egypt’s Tahrir Square.

On 11 February 2011, President Hosni Mubarak resigns his 30-year rule of Egypt.

The Arab Spring - Protests spread across Arab World (2010–2011)

Just as societies rise up against authoritarian regimes, civil unrest leads to the creation of governance vacuums. Soon, the Arab Spring is hijacked by armed militia groups and Islamist extremists.

These actors weaponise the grievances of the people, deepening conflict and all the while furthering their state-building ambitions across the Middle East and North Africa.

In Libya, rebel factions reform after the fall of Qaddafi. Comprising members from various anti-Qaddafi militias, Ansar al-Sharia (Supporters of Islamic Law) inaugurates its terrorist bid to install a totalitarian Sunni Islamic state by destroying Sufi Muslim shrines in Benghazi.

In Yemen, meanwhile, the revivalist Zaydi (Shia sect) Houthi movement is behind a siege on the town of Dammaj, which occurs in parallel to al-Qaeda’s insurgency in the country. Stepping up violent attacks in the south of Yemen, AQAP advocates for more assaults on symbols of secularism and the West.

Syria soon experiences a surge in these protest-turned-militia movements, which grow out of discontent with President Bashar al-Assad’s Ba’athist government. Within months, ethnic-based militias, pro-Assad factions, separatist groups, vigilante mobs and armed Islamist battalions take form on a daily basis – and civil war is all but a certainty.

On 2 May 2011, Osama bin Laden is killed by US Special Operations Forces in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Around the world, jihadist groups denounce the attacks.

“We condemn the assassination and the killing of an Arab holy warrior,” proclaim Hamas while a spokesman for the Taliban in Pakistan says: “If he [bin Laden] has been martyred, we will avenge his death and launch attacks against [the] American and Pakistani governments and their security forces…

If he has become a martyr, it is a great victory for us because martyrdom is the aim [for us all].”

The al-Qaeda statement says: “You lived as a good man, you died as a martyr.”

Bin Laden’s network also declares: “We will remain, God willing, a curse chasing the Americans and their agents.”

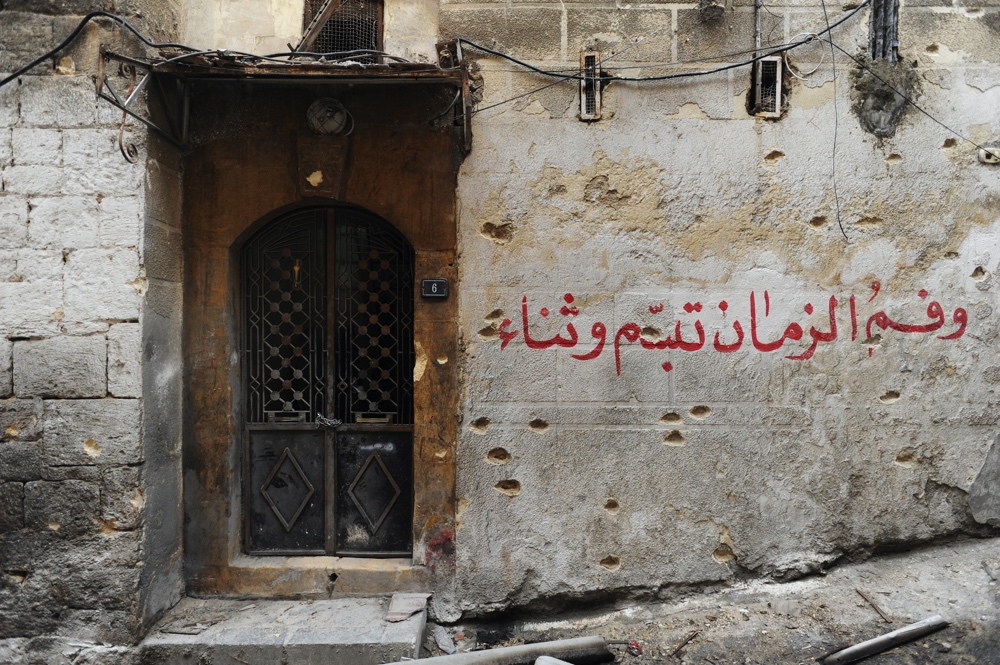

In further declarations, it states, “Soon, God willing, their happiness will turn to sadness … [and] … their blood will be mingled with their tears.”

Bin Laden’s deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri becomes the new emir of al-Qaeda.

Nine months on from the first Arab Spring protest in Syria, Abu Muhammad al-Julani (head of operations for Islamic State in Iraq) is sent on a mission by Zawahiri to establish a new al-Qaeda operation in neighbouring Syria – the Al-Nusra Front.

2012 - 2014 An Islamic State Realised

As Syria’s civil war deepens, Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan and the Arab League introduce the first major peace plan in March 2012. Further violence ensues, however, and the initiative runs aground.

Once hailed among the world’s most ethnically diverse countries – a nation of tolerance and coexistence – ethnic divisions and religion are now the main reasons why Syria’s civil war spirals out of control. Islamists, but also moderate Muslims who oppose Assad, take up arms alongside factions including Abu Muhammad al-Julani’s Jabhat al-Nusra (the al-Nusra Front). Up to 7,000 join its ranks. President Assad’s heritage – he is an Alawite, a minority sect of Shia Muslims – attracts military support from the terrorist group Hizbullah, which deploys thousands of troops from Lebanon into Syria. Kurdish and other ethnic factions also mobilise across Syria’s urban battlefields.

By October 2012, myriad armed groups have risen from the ashes of the Arab Spring, and are all competing ideologically, and territorially.

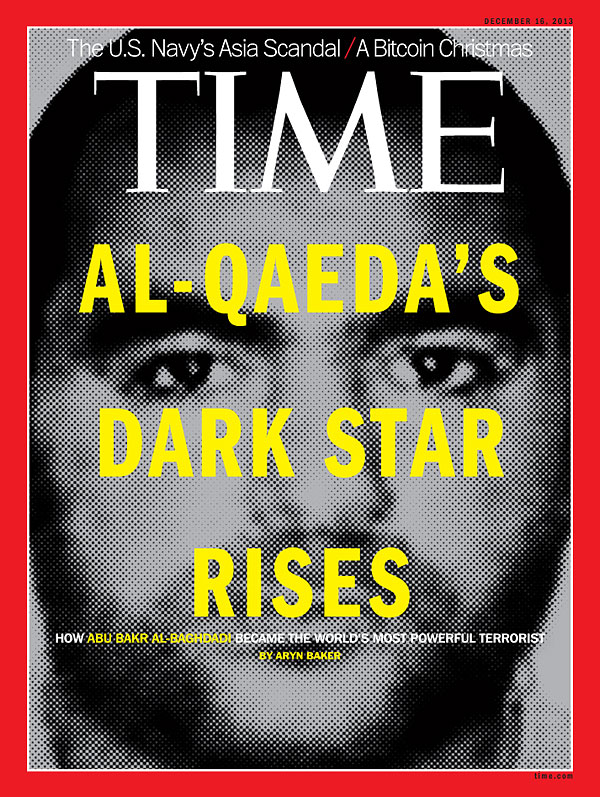

On 8 April 2013, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announces the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) will formally merge with the al-Nusra Front in Syria, creating a regional jihadist movement to be known as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham [Syria]. Baghdadi’s proposal is rejected the next day by Julani who reaffirms al-Nusra’s pledge to al-Qaeda. From hereon, al-Qaeda and ISIS outbid each other for dominance of the global jihadist movement.

As a result of the split, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) is born, with Baghdadi as the emir.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi claims to be descended from the Prophet Muhammad’s Quraysh tribe. Among many conservative Islamic scholars, this alleged lineage qualifies Baghdadi to become a caliph or leader of the Islamic State.

Across the Middle East, post-Arab Spring conditions continue to be weaponised by Islamists. In Egypt, militias comprising Bedouin tribespeople, who have complained of marginalisation for decades, now claim responsibility for violent attacks across the country.

In Yemen, there is a spike in al-Qaeda offensives on civilians, major oil pipelines and government buildings while the Houthis start to apply their ultra-extreme Shia Islamist ideals on populations across western and northern parts of the country.

In Mali, the earlier rebellions of separatists are evolving into a jihadist-led battle for territory with Iyad ag Ghali and Mahmoud Dicko spearheading hardened Islamist movements. Terrorism also continues to proliferate in Asia as the East Indonesia Mujahideen is implicated in killings and kidnappings of civilians while the Turkistan Islamic Party – formed of Uyghur Muslims seeking to recreate the ancient Turkistan empire that had once existed to the west of China – kill five civilians in a suicide attack in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. This becomes the first terrorist attack of its kind officially documented in the Chinese capital.

Despite the death of former Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar, insurgents remain in control of Afghanistan. Refusing to acknowledge Omar’s demise, the Taliban orchestrates more attacks, including on international forces when a suicide car bombing is directed at a Georgian military base in Helmand, killing seven soldiers. Ultimately, life after Omar remains unchanged, with the Taliban continuing to preserve its violent legacy and governing according to its archaic world view.

Across northern and western Iraq, ISIS expands. In Syria, the group establishes a base in Raqqah. As part of its brutal and merciless approach to obtaining territory, hundreds of civilians are massacred, security personnel executed and defectors drowned and burned alive.

Just as the Taliban did in Afghanistan during the early 1990s, ISIS justifies its bloodshed by twisting and abusing Islamic scripture.

The al-Nusra Front also begins to spearhead insurgencies in north and east Syria, competing with opposition forces and the likes of ISIS and Ahrar al-Sham. Emerging in the country at an unprecedented rate, anti-Assad, separatist, nationalist, Islamist, ethnic and a hybrid of ideologically motivated political armed groups become part of the war landscape, opening up swathes of ungovernable space, with terrorists beginning to fill the void.

ISIS Declares a Caliphate

On 29 June 2014, Baghdadi declares the establishment of a caliphate across Syria and Iraq.

The announcement of the caliphate becomes infused with historical, cultural, religious and political significance. Emulating ancient Islamic states where a caliph ruled supreme, the land now symbolises Islamic dominion in the region. For radical Islamists, the dream of a new caliphate has been long-held and hard-won against the backdrop of postcolonial legacies and unwelcome modernisation of faith and culture.

The ISIS project is perceived to stand against imperialist notions and, in so doing, attracts new generations to its rallying call for global jihad.

One week after the declaration, Baghdadi stands at a podium in Mosul’s Great Mosque to appoint himself Caliph Ibrahim.

In a 22-page open letter, more than 120 Muslim scholars, theologians and lawmakers from around the world denounce the establishment of the caliphate and condemn Baghadi’s actions. Primarily aimed at dissuading potential radicals from joining ISIS, the letter emphasises:

“You have misinterpreted Islam into a religion of harshness, brutality, torture and murder…This is a great wrong and an offense to Islam, to Muslims and to the entire world.” — Letter to Baghdadi

2014 – 2017 Promise of a Better Life

Despite jihadists perpetrating heinous, bloody crimes, many people are persuaded to leave their everyday lives and join their ranks. The cycle of violence escalates and armed factions proliferate.

In the tribal zone on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, Tehreek-e-Taliban (the group’s Pakistani offshoot) executes a siege on a school in Peshawar, killing 149 people including 132 children. This incident becomes the fourth deadliest school massacre in history; the worst was also conducted by jihadists when, in 2004, Chechen warlord Shamil Basayev sent militants to hold Russian schoolchildren and teachers in Beslan hostage.

Following the Peshawar attack, protests erupt across Pakistan to denounce Tehreek-e-Taliban and its continued persecution of Muslims, Christians and minority groups. Despite obvious public disapproval, the group continues to attract hundreds of radicals, ranging from marginalised youth to moderate Pakistanis seeking a sustainable income and welfare support.

Large parts of Basayev’s home region, in the Caucasus, also become a breeding ground for jihadists wishing to channel their anti-Russian, ultra-conservative Islamist stance into a violent terrorist agenda. By 2015, ISIS is able to establish an official base of operations in the Caucasus.

Exploiting social grievances – from poverty to disenfranchisement, oppression to feelings of marginalisation – is the primary means of recruitment used by extremists around the world.

And it is a successful tool; more than 30,000 including British, Australian, French, Spanish and US citizens travel to Syria and Iraq to take up arms with ISIS and other jihadist groups, lured with the promise of a better life, and the opportunity to live in, and die for, a “divinely sanctioned Islamic state”.

Jihadist rhetoric and propaganda material, disseminated through social media and encrypted messaging services, additionally inspire attacks on home soil.

In 2011, the French magazine Charlie Hebdo publishes a series of cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad as a caricature. Two years later, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s (AQAP) English-language magazine, Inspire, releases an assassination hit list, which includes Charlie Hebdo’s editor Stéphane Charbonnier.

Charbonnier and 11 others are shot dead on 7 January 2015 in Paris. Claiming responsibility for the attacks, AQAP’s Harith bin Ghazi al-Nadhari says the motive was “revenge for the honour” of the Prophet Muhammad.

With ISIS obtaining territory and committing merciless acts, other Islamist terrorists are inspired to adopt a similarly aggressive approach in their pursuit of their end goal, an Islamic state.

With the group’s influence on societies across the Middle East proliferating, ISIS formally declares its presence in the Libyan town of Sirte. Meanwhile, the pro-Iranian Houthis, who have violently fought for a powerful Shia base in Yemen since the 1980s, lead a coup d’état in Sanaa, ousting Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi from power and taking de-facto control of his presidential palace.

In Syria and Iraq, ISIS now holds an area extending from western Iraq to eastern Syria. Up to 12 million people reside in the self-styled caliphate and many are subjected to the brutal application of sharia law. It is estimated that 100,000 militants comprise the ranks of ISIS.

A total of 15 years after the Taliban lost its “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” to a coalition of western forces, the ISIS caliphate proves that generations of jihadists are willing to fight to resurrect notions of a medieval past.

In March 2015, ISIS announces the establishment of its Afghanistan operations – Islamic State–Khorasan Province, symbolically named after the ancient Khorasan Empire that dates back to the sixth century.

As Syria continues to descend into intractable conflict, the largest alliance of jihadists in the Middle East takes shape.

The al-Nusra Front, along with six other al-Qaeda-aligned factions, create the Jaish al-Fatah coalition or Army of Conquest.

This facilitates the consolidation of territory spanning Syria and, despite theological schisms resulting in major infighting, the country remains the global epicentre of armed Islamist extremism.

In sub-Saharan Africa, jihadism is fast becoming the biggest threat to the region’s peace, development, and security the 21st century.

Islamist Terrorism Spreads Across sub-Saharan Africa

Africa’s jihadist threat comes into sharp focus. Many fighters take up arms to become martyrs, willing to fight and die for a cause they believe is divinely sanctioned by God.

Islamist terrorism is accelerating across sub-Saharan Africa at an unprecedented rate. Civilian massacres take place in towns and villages while suicide bombings occur frequently in markets and other crowded places, and IED attacks are recorded daily on roads.

By 2017, Boko Haram’s expansion across the Lake Chad Basin displaces over 2.5 million people while up to 12 million are left requiring urgent humanitarian support in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger as a result of Islamist-initiated violence.

Conflict in the Sahel triggers mass migration into Libya and on to Europe, creating one of the largest migration crises in modern history.

While al-Qaeda and ISIS become the international face of the threat, the enemy is very much a local one. Born and raised locally, Africa’s jihadists are native speakers and deeply woven into the fabrics of their societies. Because of their backgrounds, they have an innate ability to empathise with local populations and play into their concerns relating to matters such as state corruption.

By infiltrating mosques and social circles, jihadists are able to manipulate citizens into believing their grievances are a consequence of the West and “infidel governments” and that the Islam they espouse is the one, true, pious faith. With groups including Boko Haram and JNIM in Africa, al-Nusra in Syria and Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines offering services and resources to communities, jihadists come to be regarded as leaders and viable substitutes for elected politicians.

This had been seen in Afghanistan during Mullah Omar’s tenure when policing and the provision of medical care were perceived by a small minority as the Taliban fulfilling its duty as a state actor.

Similarly, in ISIS’ Dabiq magazine, the group champions itself as a positive agent for change, claiming:

“For the first time in years, Muslims are living in security … Corruption, before an unavoidable fact of life in both Iraq and Syria, has been cut to virtually nil while crime rates have considerably tumbled.”

Governance in jihadist territory remains brutal, though, and those failing to abide by the distorted laws imposed by militants are mercilessly punished.

During 2017, at least 21 Islamist extremist groups across 15 different countries including Syria, the Philippines, Nigeria, and Yemen, execute close to 2,000 people on charges of disobedience, attempting to flee and spying. Some are killed because they belong to an “apostate” race or ethnicity whether that’s Christian, Shia, Hindu or Yazidi.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban imposes brutal punishments for so-called lifestyle offences despite losing its official power base in 2001. Nearly a third of the victims executed by Taliban militants in 2017 are accused of adultery, with the accused often stoned to death.

Al-Shabab executes at least 82 people in 2017, 18 of who are charged with being a spy.

Al-Shabab often conducts executions in front of large crowds, with announcements made on its own radio station. While staged executions are conducted to instil fear, they are also considered a way to maintain control. Thousands living in areas occupied by jihadists support these groups out of fear. Still, many others willingly endorse the terrorists. Sophisticated propaganda that romanticises violence as the means by which to restore a puritanical Islamic state coupled with generous philanthropic gestures continue to win the hearts and minds of the people.

The bid to establish an Islamic state emulating notions of past Muslim empires persists.

ISIS–Khorasan wants to reinstate the ancient Khorasan Empire in Central Asia

*Marked Red Territory

Boko Haram seeks to recreate the historical Kanem-Borno Empire in Africa

*Marked Red Territory

In June 2017, ISIS is driven out of Syria’s Mosul by Iraqi and Kurdish forces. Three months later, the group loses its base in Raqqa.

ISIS Loses its Territorial Caliphate

Many perceive its losses in Iraq and Syria to be the end of the group and its caliphate project.

But it is a symbolic demise only.

2017 – 2020 Populations Polarise

“We must give sacrifices in the fight against the crusaders. In this fight, whether we are killed, martyred or thrown in jail we are proud of it.”

Seven years after the Afghan Haqqani network makes this pledge, militants dedicated to the cause set out by founder Jalaluddin Haqqani – a former close associate of Osama bin Laden – orchestrate a car bombing in Kabul, killing more than 150 civilians. Tasked with overseeing much of the Taliban’s monetary activities and insurgent operations, the network’s attack epitomises a year of bloodshed in 2017.

This is a turning point in the history of global terrorism.

48 countries around the world record a jihadist attack and at least 84,000 people lose their lives. In Syria alone, more than 34,000 people die from Islamist terrorism and efforts made to counter it.

Inspired by narratives framing Western forces as enemies of Islam, and Muslims as holy defenders of the faith, Islamist-led attacks are documented in Manchester, London, New York, St Petersburg, Stockholm and Brussels.

ISIS claims responsibility for a vehicle ramming and stabbing assault on London Bridge on 3 June 2017, issuing the words:

“We ask Allah to accept our brothers [as martyrs], and all praise is due to Allah, the Lord of the Worlds.”

The spread of warped Islamic ideologies through borders, and across generations, has facilitated a mushrooming of new jihadist factions. It has also hardened the violent objectives of seasoned terrorist organisations. At least 121 different Islamist terrorist groups are documented as active in 2017.

Sectarianism is a motivating factor for the deadliest Islamist extremist groups. Over 95 per cent of this sectarian violence is aimed at Muslim Shia-minority populations while the Taliban, al-Shabab, ISIS and Boko Haram are among those engaging in campaigns of persecution against Christians, Hazaras and Hindus.

As terrorist groups stake claims to territory, those attempting to reach vulnerable populations are also subject to abuse, with nongovernmental organisation workers, government officials, doctors, journalists and lawyers all now targets of assassinations and kidnappings.

And yet the lure of Islamist extremism becomes ever stronger as societies polarise and populations search for alternative authority figures to guide and support them.

In December 2017, the US decision to formally recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel incites protest and anti-US sentiment on the streets of Beirut, Lebanon. Despite years of orchestrating attacks against civilians on an anti-Israel, Shia Islamist terrorist agenda, demonstrators in Lebanon come out in support of the terrorist organisation Hizbullah.

Hizbullah has maintained strong support among the Islamist segment of Shia populations in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria and Iran, but also regions beyond, where its ideologies are exported. Its provision of welfare support, Islamic education and social justice has legitimised the terrorist group in the eyes of many.

Reinforcing this belief is a calculated propaganda programme, predicated on the perceived failings and corruption of Western-supported regimes, and the benefit and duty of supporting an Islamic revolution as the only path towards justice.

Across the Middle East and Arab world, populations are drawn to Islamist extremist groups, whether through desperation or conviction.

In both Libya and Yemen, large areas are now battlegrounds for external forces.

As Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army, supported by neighbouring Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, directs efforts to overthrow the UN-backed Government of National Accord, swathes of ungoverned territory are being exploited by armed Islamist militants who are prepared to fill the void - but rule with an iron fist.

Similarly, in receiving military support from Iran, the Houthis of Yemen repeatedly launch ballistic missiles into neighbouring Saudi Arabia – a move that is calculated to deter perceived encroachment of the Sunni-based Salafi and Wahhabi sects from Saudi Arabia into Yemen. Saudi Arabia is regarded by the Houthis as part of a Western-based coalition that pursues an “imperialist agenda” and militants radicalised by the group see it as their duty to take up arms.

A Houthi slogan implores:

“God is great! Death to America! Death to Israel! Curse upon the Jews! Victory to Islam!”.

In countries such as Yemen, Libya, Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria and the Philippines, many find themselves drawn to extremist Islamist organisations. The infiltration of religious establishments, social settings and political forums combined with compelling propaganda attracts ordinary citizens, some who are willing to die for the cause. The belief that terrorists may in fact be viable alternatives for leadership of states is cultivated. Simultaneously social grievances are interpreted as the product of an un-Islamic way of life that has been influenced by Western “infidel” forces.

As militants become embedded in society, their ability to recruit and commit acts of terror becomes stronger despite security and coalition efforts.

All three suicide bombers behind a Boko Haram attack in Maiduguri, Nigeria, in May 2018 are young women; this follows the group’s deployment of at least 181 female suicide bombers in 2017 alone. While some women are kidnapped and subsequently brainwashed, others willingly join the group in support of its totalitarian world views. Similarly, jihadist groups in Somalia, Indonesia and Pakistan hire young schoolchildren to engage in militant activities.

In 2019, a suicide bomber kills more than 40 Indian soldiers in Kashmir – an attack that brings the two nuclear powers of India and Pakistan to the brink of war. The perpetrator is revealed to be a 19-year-old local Kashmiri citizen who is so disaffected by Indian occupation in the region that he joined the jihadist faction Jaish-e-Muhammad, which has close links to al-Qaeda.

Despite the loss of the ISIS caliphate in 2017, the group immediately reconstitutes in Iraq and Syria.

With an expanded network, ISIS begins to make its operations official around the world. Through locally embedded cells, the group picks up recruits across Africa and Asia as part of its global strategy.

Global Spread of ISIS (2012 – 2019)

Almost two decades on from the Bali bombings, three churches and three luxury hotels in Colombo, Sri Lanka, are targeted in a series of coordinated suicide attacks. At least 269 people are killed on Easter Sunday.

Nine bombers are identified, with most hailing from well-educated middle or upper-class families. Despite their backgrounds, the attackers believe they are defending Muslim minorities in Sri Lanka while eradicating the globalisation taking root in the country.

This “us versus the world” sentiment is praised by ISIS leader Baghdadi:

“They have put joy in the hearts of the monotheists with their immersing operations that struck the homes of the crusaders in their Easter.”

By 2020, Islamist extremists are operating across all major regions. Locals are being mobilised for terrorist operations while the ideology is inspiring attacks abroad. As this phenomenon grips new minds, the world is at its most insecure.

2020 Pandemic & Protests

Covid-19 triggers one of the largest public-health crises in modern history, and nations are forced into lockdown to contain virus spread. As a result, unemployment accelerates in most parts of the world while millions become isolated as a result of travel restrictions. New pressure points form in populations while pre-existing societal issues are heightened.

Soon, a large wave of global protests erupts.

Millions protest against racism after George Floyd is killed by a police officer on 25 May 2020.

During the unrest that ensues, at least 14,000 people are arrested and 25 killed in the US.

A blast at a storage warehouse in Beirut, Lebanon, kills 214 people on 4 August 2020.

Protests break out soon after and violent clashes against security forces are documented around the Lebanese capital.

Mass protests against Nigeria’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) take root in the country and then spread across the world in demonstrations organised by the Nigerian diaspora. At least 69 people, including 51 civilians, are killed over the course of these anti-police demonstrations.

On 6 January 2021, rioters descend on Capitol Hill to disrupt the electoral college vote count that is taking place to certify President-elect Joe Biden’s victory. Following the storming of the Capitol, 615 people are charged with federal crimes.

Events that create rifts between state and society are often exploited by jihadist groups, as exemplified by the police corruption and brutality that engendered Boko Haram’s first attack in 2009. Equally, the incompetence of certain regimes in the Middle East helped to prop up the likes of Hizbullah and the al-Nusra Front during the Arab Spring.

As unrest spreads around the world during the 2020 lockdown, Islamist terrorists create a narrative to explain events, citing “Islam” as the answer.

Shortly after the death of George Floyd, al-Qaeda publishes its One Ummah magazine, which opens with an editorial called “America Burns,” in which it describes “coronavirus, internal divisions, racism, and attacks … [as the] five corners of America’s pentagonal coffin.” The editorial goes on to state that the “last civil war marked the birth of the United States of America; this one, God willing, should mark the end.”

Attempting to court the favour of black Americans, al-Qaeda writes: “His cries of ‘I can’t breathe’ were suppressed by the sheer weight of their racist arrogance”. The editorial closes with:

“This, dear readers, is the state of America. As for the mujahideen they continue to fulfil their duty of defending their Ummah against America’s oppression by inflicting blows after blows [sic] on America.”

Extremists around the world claim the pandemic was sent to disbelievers and the West by God.

Shia militants who are part of the Yemeni Houthi movement explain coronavirus as retribution for the Western world’s insistence that the “faces of Muslim women must be revealed, even though Allah ordered women to cover their faces.”

Meanwhile, an audio message by Boko Haram’s Abubakar Shekau states that the spread of Covid-19 can be blamed on the “evil that you do,” adding that he and his followers are protected from the virus because “we pray five times a day.”

Hizbullah adopts a similar narrative to manipulate supporters, proclaiming that “fasting strengthens patience” and “with patience we can beat coronavirus, defeat the Israeli enemy and overcome other major challenges.”

Terrorist groups around the world begin to exploit the pandemic for their own benefit. In Somalia, al-Shabab initially dispels the virus as a “plague” that is sent to punish enemies, describing it as “divine punishment” for non-believers. But by June 2020, the group announces:

“Al-Shabab’s coronavirus prevention and treatment committee has opened a Covid-19 centre.”

Limited security and travel restrictions mean that state-led and international efforts to reach vulnerable citizens contending with Covid-19 are ineffective, so jihadist groups fill the void.

Anti-Coronavirus campaign by Health Commission in Kunduz pic.twitter.com/wNfeKGlrsy

— Zabihullah (..ذبـــــیح الله م ) (@Zabehulah_M33) March 29, 2020

The Taliban distributes surgical masks and gloves while conducting workshops to educate followers on hygiene and social distancing. Hayat Tahrir al-Sham – formerly the al-Nusra Front – sterilises schools, mosques and government buildings while qualified doctors who have joined the terrorist group hold forums to explain the group’s Covid-19 plans.

Militants have traditionally garnered popular support by offering free welfare, education, criminal justice and medical care to citizens in their territories. While Covid-19 presents an opportunity to delegitimise the role of government and Western forces, it is also another opening through which to legitimise the pursuit of an Islamic state.

Against the backdrop of the pandemic, Islamist terrorist attacks continue to be documented around the world. France, Germany, Austria and the United Kingdom all suffer Islamist-inspired violence.

In April, ISIS claims its first-ever attack in the Maldives after arson destroys five boats. Weeks later, the group releases a video called “Incite the Believers”. It encourages jihadists to use fire to destroy agricultural fields, buildings, factories and forests.

Terrorist insurgencies also continue amid lockdowns. In Mozambique, ISIS-aligned group Ansar al-Sunna beheads 50 villagers in Cabo Delgado – the worst attack since the group officially formed in 2017. One month later, in November 2020, 110 civilians are killed by Boko Haram in Koshebe, Nigeria. It is one of the bloodiest mass killings by Boko Haram since the group’s inception in 2003.

The pandemic forces several nations to temporarily draw down overseas troops, prompting jihadists to issue statements calling on sympathisers and militants to exploit the situation.

JNIM, which formed in 2017 but whose militant leaders, Iyad ag Ghali and Amadou Koufa, had been active in the Sahel since the 1990s, declares that Europe is suffering due to “exhaustion from the Covid-19 pandemic” and that it has struck the “ranks of the invading forces in Mali”. The alliance of jihadists also emphasises how it hopes the virus will eliminate coalition forces so that lands would be returned to the “Muslims”.

Similarly, upon the announcement by President Donald Trump that the US will withdraw troops from Afghanistan in 2021, the new leader of AQAP, Khalid bin Umar Batarfi, makes a rallying call to militants around the world and to al-Qaeda’s global network:

“If the mujahideen were patient in Sham, Palestine, Syria, the Arabian Peninsula, Somalia, and the Islamic Maghreb” then “Allah will show us what we have seen in Afghanistan, and He will break the thorn of the enemies everywhere”.

JNIM – whose formation had been overseen by al-Qaeda’s deputy emir, Ayman al-Zawahiri – also takes advantage of the US troop-withdrawal announcement, romanticising the efforts of previous jihadists and also pre-empting a Taliban victory in Afghanistan. “Mullah Omar, may Allah have mercy on him, said his timeless words: Verily Allah promised us with victory and America has promised us with defeat, and we will see which of the two promises is fulfilled”.

Ultimately, jihadists the world over welcome the announcement of troop withdrawal.

Now The Threat Today

Before 9/11, many perceived Islamist violence to be limited in scope and geography: mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan, wars in Iraq and Iran, and bombings of Israeli positions.

The Battle of Mogadishu in 1992 – which precipitated the fall of Somalia’s government – and the rise of the Taliban regime, inaugurated with the torture and execution of the country’s former president Mohammed Najibullah, portrayed an Islamist threat that was destructive; even so, that threat was still regarded as confined to parts of the world prone to underdevelopment and instability.

There were indeed high-profile isolated incidents: the massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics; the shooting of tourists at the gates of Luxor, Egypt, by Islamists in 1997; and the first bombing of New York’s World Trade Centre, in 1993.

But 9/11 prompted the world to take notice of an increasingly violent threat that was steadily growing more dangerous.

Islamist extremism has evolved and proliferated since 2001.

Osama bin Laden’s world view that a holy war should be waged against the West and that Muslims should:

“fight the pagans all together … until there is no more tumult or oppression”

…hardened the violent ambitions of jihadists at the time.

It also inspired a new generation of militants, ideologues and terrorist leaders who carry attacks all over the world.

From Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines to ISIS in Egypt, JNIM in the Sahel to the Turkistan Islamic Party in China, the roots of today’s jihadist groups stretch as far back as the 1970s. But their current, more violent incarnations are a product of their operational reinvention in the 2000s, after the events of 9/11.

In Africa, Somalia is now under siege by the al-Qaeda aligned al-Shabaab, Boko Haram is steering a transnational insurgency across the Lake Chad Basin, and the expansion of Islamist extremism in the Sahel has created one of the world’s largest humanitarian crises. Similarly, Yemen has seen a revived Shia Houthi movement while Libya is now plagued with warring armed Islamist factions vying for territory.

Mozambique, Tunisia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Kashmir are all emerging as new hotspots for Islamist violence, while Iraq and Syria continue suffer from jihadist terrorism on a daily basis.

In the UK, Spain, France, Belgium, Australia, China, India and Sweden, the worst acts of Islamist terrorism have occurred since 9/11.

Today, more than 60 countries are affected by Islamist terrorism, and over 100 Islamist factions are operational globally.

Six of the world’s largest conflict zones – Afghanistan, Libya, Sahel, Somalia, Syria, Yemen – are all spearheaded by Islamist extremists.

Both ISIS and al-Qaeda now have a presence in at least 25 countries.

This militancy spans at least four generations. Ageing jihadist veterans who took up arms in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s are now shaping the minds of today’s youth, imparting a narrative that the West and its allies are infidel forces to be destroyed, that internationalism is un-Islamic and sinful, and that the best way to preserve a pure, authentic Islam as “professed” by God is to eliminate any non-believers and dissidents.

Extremists also frame social grievances as a consequence of governments and faith in democratically elected political leaders, which helps to legitimise the state-building work of armed Islamist groups. By promising free education, health care, welfare support and policing services, terrorist groups manipulate society into believing that they can lead and govern.

This is what mobilises thousands of people to support jihadist groups and their merciless pursuit of restoring a medieval-style Islamic state – one that is governed by brutal applications of sharia law.

The Taliban achieved this in 1996, as did ISIS in 2014. Despite both groups losing their territories, Islamist extremists continue to regard being a holy warrior, and martyr, for this cause as the ultimate sacrifice.

Following the February 2020 announcement that US troops are to withdraw from Afghanistan, territory begins to be contested in areas that were previously kept secure by Afghan government forces and their allies.

In May 2021, President Biden announces the US will withdraw unconditionally from Afghanistan.

The Taliban immediately launches a rapid offensive, and in July, militants capture 64 districts, entering Afghanistan’s second- and third-largest cities, Kandahar and Herat. Taliban militants ensure their pursuit of territory is bloody and merciless. In capturing Faryab province, 22 unarmed soldiers who surrender to the Taliban are summarily executed by gunfire. Celebrating the murder of the troops, militants shout “Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar”.

Allied nations including Germany and Italy soon begin to withdraw troops from the country, and on 6 August, the Taliban captures the provincial capital of Nimruz, Zaranj. It becomes the first provincial capital to fall under Taliban control since the 2001 US invasion. Four days later, nine more provincial capitals fall to the jihadists.

Militants take control of Jalalabad, Nangahar, on 15 August; Kabul remains the last major city under government control.

Afghanistan: Territorial Presence of Taliban

No Taliban presence

Taliban presence

Taliban control

Nineteen years after the Taliban lost power in Afghanistan, militants finally take over Kabul and force President Ashraf Ghani into exile.

The Taliban declares an Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan once again.

The Taliban achieves what all jihadist groups desire: the establishment of an Islamic state and defeat of America and its allies. It prompts terrorist organisations around the world to celebrate the Taliban’s “victory”

Militants of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) – formerly the al-Nusra Front – drive through the streets of Idlib, Syria, waving Taliban flags and distributing sweets to locals. Hamas also celebrates the Taliban’s territorial accomplishments, stating:

“we congratulate the Muslim Afghan people for the defeat of the American occupation on all Afghan lands."

Al-Shabaab, who have been on a 15-year violent campaign to establish an Islamic state in Somalia, praise the Taliban after the declaration of an Islamic Emirate. Broadcasting on its Andalus radio station, the group states, “the conflict in Somalia resembles that in Afghanistan”; it also warns Turkey, which is providing support to the government of Somalia, to immediately leave, claiming:

“the American experience in Afghanistan is the fate threatening every country occupied by foreign forces”.

“The graveyard of empires and superpowers” AQAP on Afghanistan after the Taliban claims victory.

Alluding to the never-ending battle to realise an Islamic state around the world, AQAP highlights the Taliban’s efforts in Afghanistan as just the start: “We are optimistic that this conquest, empowerment and historic event is the first of what will follow of conquests”.

The Taliban in control of Kabul in August 2021 is structurally different to the mujahideen that assumed power in 1996. This group is in a far stronger position economically after establishing a deep presence in the country’s resource-rich areas; it has also learned the art of virtue-signalling PR, and the need to portray their operations as inclusive and peaceful.

Days after the Taliban takes control, its spokesman vows in a televised interview to respect women’s rights – despite TV being banned during its government in the 1990s and Afghan women enduring some of the worst human-rights violations in recorded history while the group were in power.

Despite this carefully orchestrated PR campaign, summary executions and allegations of human-rights abuses – including systematic sexual assaults of females by Taliban militants – have already been documented in the country.

Taliban leaders are trying to paint a different picture of what life under their new regime will be like. But ultimately, the group retains the same violent ideologies as its previous incarnations.

Its supreme leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada, is a former mujahideen fighter from the 1980s and was part of the Taliban’s controversial “vice and policing” unit that implemented the group’s Islamic laws. This included physical punishments for people who drank alcohol and females who were not fully covered.

Akhundzada was an advisor to Taliban founder Mohammed Omar.

Omar’s legacy runs deep in this “new” Taliban. Its first deputy, Abdul Ghani Baradar, was friends with Omar as a teenager, later becoming his right-hand man in the mujahideen, while the second, Mohammad Yaqoob, is Omar’s son – once hailed by the Taliban as “our hero, the son of our great leader”.

Lineage and familial relations can also lead to inheritance of a position of power in jihadist groups. Boko Haram appointed its founder’s son, Abu Musab al-Barnawi, as its leader in 2016, while Hamza bin Laden, son of Osama bin Laden, was emerging as an al-Qaeda leader before his death in 2019. In appointing a third deputy, the Taliban looks to Sirajuddin Haqqani – son of Jalaluddin Haqqani of the Haqqani network.

Many Afghans today were not alive to experience Taliban rule in the 1990s; they witnessed neither the brutal and indiscriminate application of sharia law nor the group’s looming violent presence across the country. In the past 20 years, more than 2.2 million citizens have been made refugees and many more are now attempting to flee, faced with the prospect of the Taliban’s return to power and all it could entail.

Yet a parallel generation of young people exists. They too have grown up in the post-9/11 world but will look up to older Taliban militants, perceiving them as heroes and martyrs who over time have toppled both an “apostate” Afghan government and the West.

The influence of such groups on sections of today’s youth should not be underestimated. By catering to anxieties about the erosion of Muslim identity, by romanticising violence and abuse as a means to achieving the ideal of an Islamic state, and by foregrounding brutal and extreme applications of sharia law, ISIS, al-Qaeda and others continue to win hearts and minds.

In the world of an Islamist extremist, internationalism and global outlooks are considered perverse, sinful, even malevolent. Duty is equated to martyrdom. Barbarism is hidden beneath the veil of a twisted ideology that purports to represent a religion.

This is why it has never been more important for communities to identify the peaceful ties that bind them together, to rally and to reject this extremism.

Inclusivity, diversity and receptiveness to change were once the uniting hallmarks of fabled Muslim communities; they can be once more.

To inspire hope among the next generation – not to overlook or discount their concerns and anxieties – the world must find common ground, work at a local community level to improve social contracts and develop inspiring shared narratives to counter extremism.

So much depends on the steps that are taken today to ensure a brighter future for generations to come.